SS Marine Electric

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

(Redirected from

Marine Electric)

|

| Career (USA) |

|

| Name: |

- Musgrove Mills (1944–47)

- Gulfmills (1947–1961)

- Marine Electric (1961–83)

|

| Owner: |

- U.S. Maritime Commission (1944–47)

- Gulf Oil Corp. (1947–61)

- Marine Transport Lines Corp. (1961–83)

|

| Port of registry: |

Wilmington, Delaware |

| Builder: |

Sun Shipbuilding & Drydock Co., Chester, Pennsylvania |

| Yard number: |

437 |

| Laid down: |

10 January 1944 |

| Launched: |

2 May 1944 |

| Completed: |

23 May 1944 |

| Identification: |

Official number: 245675 |

| Fate: |

Foundered, 12 February 1983 |

| General characteristics |

| Class & type: |

Modified Type T2-SE-A1 tanker |

| Tonnage: |

- As built:

- 10,448 GRT

- 16,613 DWT

- After 1962:

- 13,757 GRT

- 25,575 DWT

|

| Length: |

- As built:

- 523 ft (159 m)

- After 1962:

- 605 ft (184 m)

|

| Beam: |

- As built:

- 68 ft (21 m)

- After 1962:

- 75 ft (23 m)

|

| Propulsion: |

Turbo-electric, 6,000 shp (4,474 kW) |

| Speed: |

15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph) |

| Range: |

12,600 nmi (23,300 km; 14,500 mi) |

SS Marine Electric, a 605-foot

bulk carrier, sank on 12 February 1983, about 30 miles off the coast of

Virginia,

in 130 feet of water. Thirty-one of the 34 crewmembers were killed; the

three survivors endured 90 minutes drifting in the frigid waters of the

Atlantic. The wreck resulted in some of the most important maritime

reforms in the second half of the 20th century. The tragedy tightened

inspection standards, resulted in mandatory survival suits for winter

North Atlantic runs, and helped create the now famous Coast Guard rescue

swimmer program.

Ship history

The ship was built by the

Sun Shipbuilding and Drydock Company of

Chester, Pennsylvania for the U.S. Maritime Commission (contract No. 1770) as a

Type T2-SE-A1 tanker, hull number 437. She was laid down on 10 January 1944, launched on 2 May, and delivered on 23 May.

[1]

In May 1947, she was sold to the

Gulf Oil Corporation and renamed

Gulfmills. In May 1961, she was purchased by

Marine Transport Lines (MTL), and renamed

Marine Electric. The ship was modified by the addition of a new midsection for cargo transport, built at the

Bremer Vulkan yard in Bremen, Germany, which was then towed to the Bethlehem Steel Co. yard in

East Boston. This extended the ship's

length overall from 523 feet (159 m) to 605 feet (184 m), and her tonnage from 10,448 to 13,757

gross register tons (GRT). The work was completed in November 1962.

[2] However, the

Marine Electric was showing its age, exhibiting corrosion and damage to the hull and other structural components.

Final voyage

The

Marine Electric put to sea for her final voyage on 10 February 1983, sailing from

Norfolk, Virginia to

Somerset, Massachusetts with a cargo of 24,800

tons of granulated coal. The ship sailed through a fierce (and ultimately record-breaking) storm that was gathering.

The

Marine Electric neared the mouth of the

Chesapeake Bay

at about 2:00 a.m. on Thursday, 10 February. She battled 25-foot

(7.6-m) waves and winds gusting to more than 55 miles per hour

(89 km/h), fighting the storm to reach port with her cargo.

The following day, she was contacted by the

United States Coast Guard to turn back to assist a fishing vessel, the

Theodora, that was taking on water. The

Theodora eventually recovered and proceeded on its westerly course back to Virginia; the

Marine Electric turned north to resume its original route.

During the course of the investigation into the ship’s sinking,

representatives of MTL theorized that the ship ran aground during her

maneuvering to help the

Theodora, fatally damaging the hull. They contended that it was this grounding that caused the

Marine Electric to sink five hours later.

But Coast Guard investigations, and independent examinations of the wreck, told a different story: the

Marine Electric

left port in an un-seaworthy condition, with gaping holes in its deck

plating and hatch covers. The hatch covers, in particular, posed a

problem, since without them the cargo hold could fill with water in the

storm and drag the ship under. And it was there that the investigation

took a second, dramatic turn.

Investigators discovered that much of the paperwork supporting MTL's declarations that the

Marine Electric

was seaworthy was faked. Inspection records showed inspections of the

hatch covers during periods where they'd in fact been removed from the

ship for maintenance; inspections were recorded during periods of time

when the ship wasn't even in port. A representative of the hatch covers'

manufacturer warned MTL in 1982 that their condition posed a threat to

the ship’s seaworthiness. But inspectors never tested them. And yet, the

Marine Electric was repeatedly certified as seaworthy.

Part of the problem was that the Coast Guard delegated some of its inspection authority to the

American Bureau of Shipping. The ABS is a private, non-profit agency that developed rules, standards and guidelines for ship's hulls. In the wake of the

Marine Electric

tragedy, questions were raised about how successfully the ABS was

exercising the inspection authority delegated to it, as well as about

whether the Coast Guard even had the authority to delegate that role.

Also there was a conflict of interest in that the inspection fees paid

to the ABS were paid by the ship owners.

Aftermath

In the wake of the

Marine Electric sinking,

The Philadelphia Inquirer

assigned two reporters, Tim Dwyer and Robert Frump, to look into old

ship catastrophes. In the series, the writers concluded that government

programs designed to strengthen the merchant marine had actually kept

unsafe ships afloat. Frump later wrote a book,

Until the Sea Shall Free Them, about the sinking.

In the wake of the Marine Board report, and the newspaper's

investigation, the Coast Guard dramatically changed its inspection and

oversight procedures. The Coast Guard report noted that the ABS, in

particular, "cannot be considered impartial", and described its failure

to notice the critical problems with the ship as negligent. At the same

time, the report noted that "the inexperience of the inspectors who went

aboard the

Marine Electric, and their failure to recognize the

safety hazards...raises doubt about the capabilities of the Coast Guard

inspectors to enforce the laws and regulations in a satisfactory

manner."

While the Coast Guard commandant did not accept all of the

recommendations of the Marine Board report, inspections tightened and

more than 70 old World War II relics still functioning 40 years after

the war were sent to scrap yards. In 2003, Coast Guard Captain Dominic

Calicchio was posthumously awarded The Plimsoll Award by

Professional Mariner magazine in part because of his role as a member of the Marine Board of Investigation.

[3]

Additionally, the Coast Guard required that survival suits be

required on all winter North Atlantic runs. Later, as a direct result of

the casualties on the

Marine Electric, Congress pushed for and the Coast Guard eventually established the now famous

Coast Guard Rescue Swimmer program.

Though the safety of sailors at sea improved in the wake of the

Marine Electric

tragedy, those improvements in safety came at the expense of 31 lives,

condemned to a watery grave by poor maintenance and inadequate

governmental oversight.

See also

References

External links

- A firsthand account of the wreck by Bob Cusick, one of the surviving crew members

-

Cold Comfort

By Bob Cusick

February is the shortest month of the year, it's true. But for me, a few hours in

February-on the 12th day, in the year 1983-seemed an eternity. The winter wind, blown by

what the weather bureau later classified as "the worst East Coast storm in 40

years," whipped the ocean into a fury. The ship I was on, the Marine Electric, was on

its way from Norfolk, Virginia, to a power station in Somerset, Massachusetts, carrying a

load of coal. 1, the Marine Electric's Chief Mate, was just shy of my 60th birthday, and

had been a seaman since 1941. But in all that time, I had never been on a voyage like this

one. Although a snowstorm was brewing when we loaded the vessel just a day and a half

earlier, we expected a routine voyage. Neither my 33 shipmates nor I imagined then that we

would share the most terrifying experience of our lives.

The 605-foot Marine Electric, scheduled for dry-docking that spring, had been patched

together in 1962 from the bow and stem of a World War H-vintage tanker and a new mid-body

built in Germany. Everything on the ship was battened down and secured when I turned in

for bed at 2330 hours the previous night. At about 0 1 15 hours, Duty Mate Richard Roberts

had noticed that the bow was not rising properly to the seas. First Engineer Michael Price

had responded by putting the pumps on to the forward tanks. But the pumps couldn't keep

ahead of the water. A worried Captain Philip Corl awoke me at 0230 hours "Come up to

the bridge, Mate," he said. "I can't really tell, but I think she's settling by

the head." He was right. The ship had evidently fractured or opened up forward.

Soon it became apparent that the ship was losing her transverse stability: She was

taking a starboard roll and not returning upright. Captain Corl gave the orders to prepare

to abandon ship. The crew was mustered at the starboard lifeboat, on

"Cold Comfort" by Bob Cusick Page 2 of 4

the low side. At 0413 hours, as the ship was taking an even more pronounced list, the

captain blew the whistle. We began to lower the boat. The sea was cresting at 20-25 feet.

I remember thinking that, with the condition of the wind and sea and the position of the

ship, there was only a slight chance of a successful

launching.

As we were lowering the lifeboat, the ship--seemingly instantly--rolled right down on

her beam's end. I found myself, along with most of the crew, trapped under the deck house,

in the dark, 39-degree water.

Having done much snorkeling since I was a youth, I could hold my breath for long

stretches, and to this I attribute my ability to swim out from under the ship while so

many could not. When I finally broached the surface of the seas, I was faced with a dim

prospect: the night was as dark as pitch, and the icy ocean tumultuous, and the air

temperature a mere 29 degrees. I scanned the area and, in the frigid air, was able to make

out the shape of the ship's smokestack. It was now almost horizontal, and I could hear the

seas slopping against it. I struck out, afraid of being sucked down as the ship continued

to sink.

As I swam, the waves would crest and break, causing me to stop and hold my breath. Each

time a wave cleared, I would swim some more until the next one came. I was not really

conscious of time, but found myself being focused by some innate survival instinct. In

time, I came across a large lifeboat oar and grabbed onto it.

Then suddenly, something happened that I've never been able to explain-at least not

with conventional logic. As I clung to the oar, I felt a line wrap about my right leg,

just above the ankle. Holding onto the oar with one hand, I tried to untangle myself from

the line, but found that I could not. A strong tension pulled on it. The line felt like a

type known as a nine-thread, which is commonly used for heaving lines and attaching life

rings. But if the line were attached to a life ring, it would be floating; and in any

case, there should be no tension. As it was, though, I felt the line pulling me sideways

so strongly that, had I not maintained a strong grip on the oar, I'd have been yanked off

of it.

Page 3 of 4

"Cold Comfort" by Bob Cusick

After a long, cold while, I discerned a shape in the distance. No moon or stars shone.

The only light was the glow of spindrift on the water's surface, and the shape seemed to

be just a slight variation of the darkness that surrounded me. While focusing on the

silhouette, I realized that the line was gone from my foot. Still clinging to the oar, I

swam toward the shape and, as I approached, I was able to identify it. It was a lifeboat,

mostly submerged. It disappeared from sight each time a wave broke over it, until I

finally reached the craft. Then, I discovered that it was tom wide open; air tanks were

keeping it afloat.

No sooner had I climbed in and wrapped my legs around a thwart than a wave crashed

down, nearly washing me out. When it cleared, the bitter wind hit, and I realized that, if

I stayed in the open air, I would soon freeze to death. So I submerged myself in a

water-filled portion of the boat, wedged my body under a seat, and waited, praying for

daylight and a chance of being rescued.

The crashing waves took longer to clear from the lifeboat than they did in the open

sea. Often, when water inundated the boat, it took so long to flow out that I despaired of

being able to ever breathe again. After a time, I became exhausted, and I was increasingly

tempted to let go. Just breathe in the water, I thought; the struggle will be over. It

will be peaceful.

At one such a time, as I labored through a retreating wave, the words of a song that I

had learned the previous summer came into my mind. The song, by Canadian folk musician

Stan Rogers, was inspirational, and particularly fitting. Called "The Mary Ellen

Carter," it told the story of a shipwreck. Soon I was shouting out the chorus,

"Rise again! Rise again!" singing on through the long, lonely night whenever the

icy seas broke away.

As I alternately sang and held my breath, the bone-chilling waves sweeping me up and

washing over me, many thoughts helped keep me from giving up. I recalled that the captain

had notified the Coast Guard of our situation as the ship was sinking. I reflected on what

I knew of Coast Guard actions in the past, and considered their motto, "you have to

go out, but you don't have to come back." And I had faith that they were on the way,

and that they would do everything possible to find me.

Page 4 of 4

"Cold Comfort" by Bob Cusick

At about 0700 hours, with the sun just breaking the horizon, the angel of mercy, in the

form of the United States Coast Guard Helicopter No. 147 1, appeared overhead. The crew

had spotted me, like a grain of sand on a beach (for I had drifted far from the ship), and

plucked me from the freezing water. Aboard were the only other survivors: Paul Dewey, Able

Seaman, who was also able to swim out from under the ship; and Eugene Kelly, Third Mate,

who was on the bridge when the ship rolled over. Also on board were the bodies of several

of our Marine Electric shipmates. The helicopter brought us to Peninsula General Hospital

in Salisbury, Maryland, where we recovered from the effects of the ordeal. Meanwhile,

Coast Guard vessel crews recovered the battered bodies of our remaining shipmates, except

for seven that were never found.

Following that experience, I lived-as I had 25 years previously--on the seacoast, in

Scituate, Massachusetts. But storms were never the same for me afterward. Every time a

gale threw waves crashing onto the beach, 1, snug in the house, would return in thought to

the early hours of 12 February 1983. I'd remember the seas washing over the lifeboat,

holding my breath until they 'cleared, knowing how easy it would be to just let go and

slip under the water. And I'd remember feeling the guidance of the mysterious line, and

being buoyed by a dozen or more inspirational forces, including a song and visions of a

Coast Guard rescue.

I hope that we never take for granted the men and women of the Coast Guard. What they

do is among the bravest and most selfless work to which people can dedicate their lives.

It is because of their sense of duty and courage that I am here today, and I will never

forget it. All of the people who go to sea-whether on Navy or Merchant ships, in fishing

boats, yachts, or any other craft-know, too, that the Coast Guard is on call in case of

emergency.

Next time the winds start howling and the seas begin heaping up, I'll be thinking (and

perhaps you will, too): Maybe a distress signal will come from a vessel in danger. If so,

the crews of the Coast Guard will be out in cutters and helicopters, risking their own

safety while doing all they can to save lives in peril.

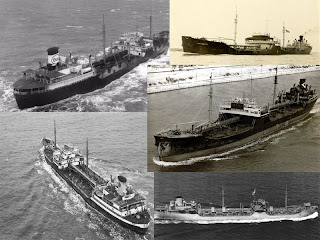

- Archive of T2 Tankers

-